Chart of Accounts for Nonprofits: Build a Better System

Discover a chart of accounts for nonprofits that streamlines reporting and boosts transparency.

Your nonprofit chart of accounts is the backbone of your financial system. Think of it as a complete, organized list of every account in your general ledger, designed to tell your organization's story through numbers. It’s the essential tool that tracks every dollar you own, owe, earn, and spend, making it foundational for accurate reporting, grant management, and overall financial health.

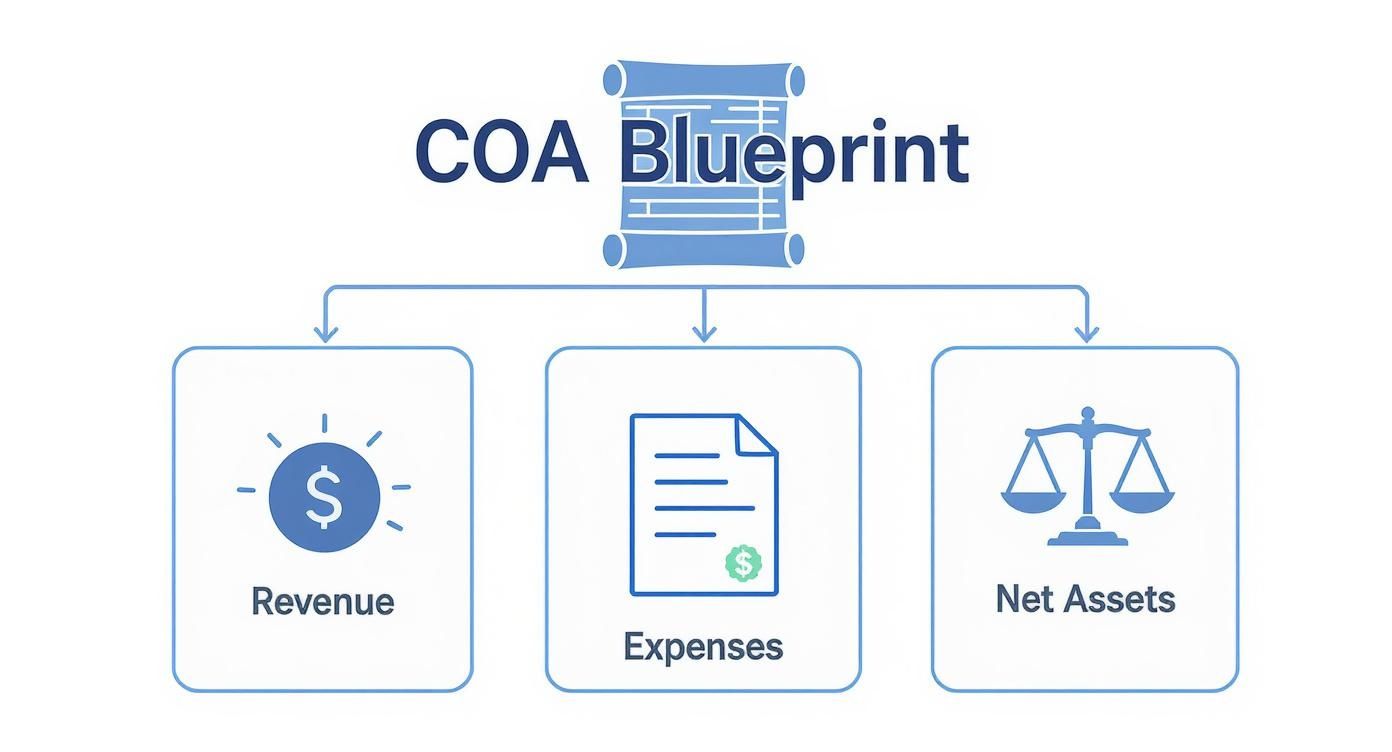

Why Your Chart of Accounts Is Your Financial Blueprint

Ever tried to build something without a plan? Imagine constructing a house without a blueprint. You'd have no idea where the foundation should go, how the rooms connect, or if the whole thing will even stand up. A nonprofit's chart of accounts (COA) serves that exact same purpose for your finances—it’s the architectural plan that brings order and clarity to everything you do.

Without a solid COA, your financial data quickly becomes a jumbled mess of transactions. This makes it incredibly difficult, if not impossible, to generate meaningful reports for your board, donors, or grant funders. This isn't just a hypothetical problem; while around 90% of nonprofits collect financial data, a shockingly low 5% actually use it to make strategic decisions. A well-designed COA is the bridge that closes this gap, turning raw data into powerful insights. You can discover more insights about this nonprofit data challenge and how to overcome it.

The Five Core Account Types

At its heart, every nonprofit chart of accounts is built from five fundamental account types. Getting a handle on these categories is the first step toward really understanding your organization's financial story. Each one answers a different, crucial question about your financial position and day-to-day activities.

These five core types are:

- Assets: What does our organization own? (e.g., cash in the bank, buildings, equipment).

- Liabilities: What do we owe to others? (e.g., loans, unpaid bills, payroll taxes).

- Net Assets: What is our organization’s net worth? This is the difference between assets and liabilities and is the nonprofit version of "equity" in a for-profit company.

- Revenue: How does our organization bring in money? (e.g., donations, grants, program fees).

- Expenses: What do we spend money on to fulfill our mission? (e.g., salaries, rent, supplies).

A well-organized COA is the foundation for every financial report, grant proposal, and strategic decision you make. It translates your mission's activities into a clear, universally understood financial language.

To help you see how these pieces come together, the table below gives a quick summary of each account category, its standard numbering range, and a few common examples you’d see in a typical nonprofit chart of accounts.

Core Account Types in a Nonprofit Chart of Accounts

| Account Category | Typical Number Range | What It Tracks | Example Accounts |

|---|---|---|---|

| Assets | 1000s | What your organization owns | Cash, Accounts Receivable, Buildings, Equipment |

| Liabilities | 2000s | What your organization owes | Accounts Payable, Loans, Accrued Expenses |

| Net Assets | 3000s | Your organization's net worth | Unrestricted, With Donor Restrictions |

| Revenue | 4000s | Income your organization earns | Individual Donations, Grants, Program Fees |

| Expenses | 5000s and up | Money your organization spends to run its programs | Salaries, Rent, Utilities, Program Supplies |

This simple, logical structure is the key to unlocking clear and consistent financial storytelling for your organization.

Mastering Fund Accounting Within Your COA

While for-profit businesses are all about tracking profitability, a nonprofit’s financial system is built on a different principle: accountability. This is the world of fund accounting, and it's the single biggest reason a nonprofit chart of accounts looks so different from a corporate one. Think of it as an ethical and legal promise you make to your donors, built directly into your books.

Imagine every restricted donation you receive comes in its own specially marked envelope. A donor gives you $5,000 specifically for the youth summer camp. That money goes into the “Summer Camp” envelope, and it can only be used for expenses tied to that program. Fund accounting is simply the system you build to create and keep track of all these envelopes, making sure every dollar is spent exactly as the donor wished.

Your chart of accounts is the framework for this system. It’s what prevents you from accidentally using money from the "Summer Camp" envelope to pay the church’s electric bill. Get this right, and you build incredible trust with your supporters—the very foundation of good stewardship.

Understanding Net Assets With and Without Donor Restrictions

To properly manage these "envelopes," nonprofit accounting splits its net assets (the nonprofit version of "owner's equity") into two main buckets. These categories aren't just a good idea; they're required by Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) for transparent reporting.

Net Assets Without Donor Restrictions: This is your general operating money. It comes from sources like undesignated tithes, offerings, or program fees. Your organization has the freedom to use these funds for any part of its mission, from paying staff salaries to buying office supplies.

Net Assets With Donor Restrictions: This is the cash inside those designated envelopes. The donor has placed a specific limit on its use. It might be tied to a program (like the summer camp), a time frame (to be spent next year), or a purpose (for a new building).

A well-designed chart of accounts must clearly separate these two types of funds. This structure is absolutely critical for creating accurate financial statements and proving your financial integrity to auditors, your board, and your donors.

A dollar is rarely just a dollar in the nonprofit world. Fund accounting, reflected in your COA, is the mechanism that honors the specific intent behind each contribution, turning a simple transaction into a fulfilled promise.

To see how these ideas come together, here's a simple map showing how revenue, expenses, and net assets all connect within a properly structured COA.

This blueprint shows how a solid COA organizes every financial event into the right category, laying the groundwork for reporting that everyone can trust.

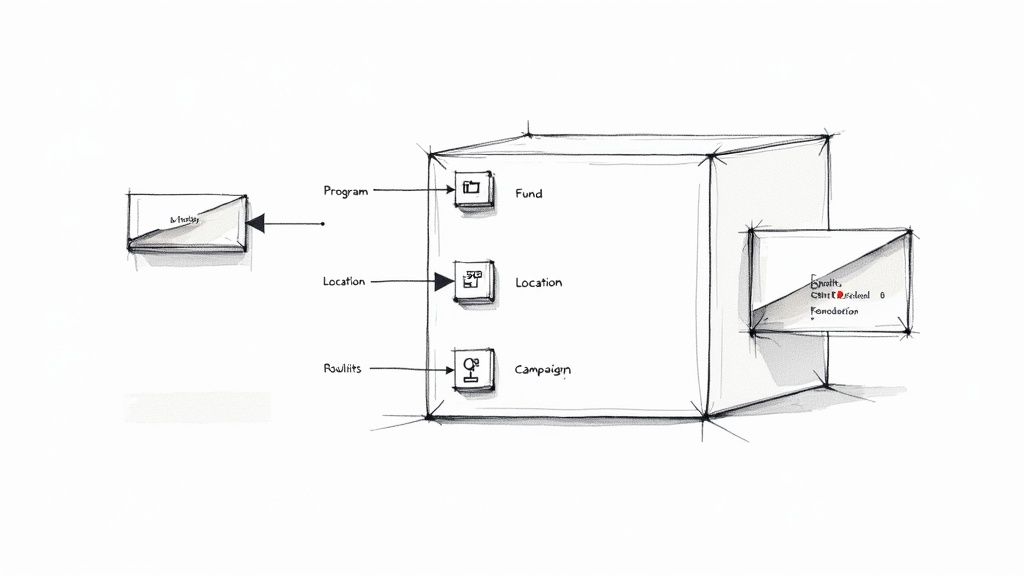

How Segments and Dimensions Bring Clarity to Funds

In the old days, organizations would create hundreds of different general ledger accounts to track every single fund, grant, and program. The result? A bloated, unmanageable chart of accounts that was a nightmare to work with.

Thankfully, modern accounting software gives us a much cleaner solution: segments or dimensions.

Instead of creating a long, clunky account like "5510-Youth Program-Salaries-Smith Grant," you just use one simple expense account: "5510-Salaries." Then, you "tag" that transaction with dimensions like the program ("Youth Program") and the funder ("Smith Grant"). This keeps your COA lean and easy to manage while giving you incredibly powerful reporting.

You can instantly run a report to see all expenses by program, by funder, or even by location, all without cluttering your core list of accounts. If you want to dig deeper into the official reporting standards that drive these classifications, you can learn more about FASB ASC 958 in our detailed guide. This modern approach turns your chart of accounts from a static list into a dynamic tool for true financial insight.

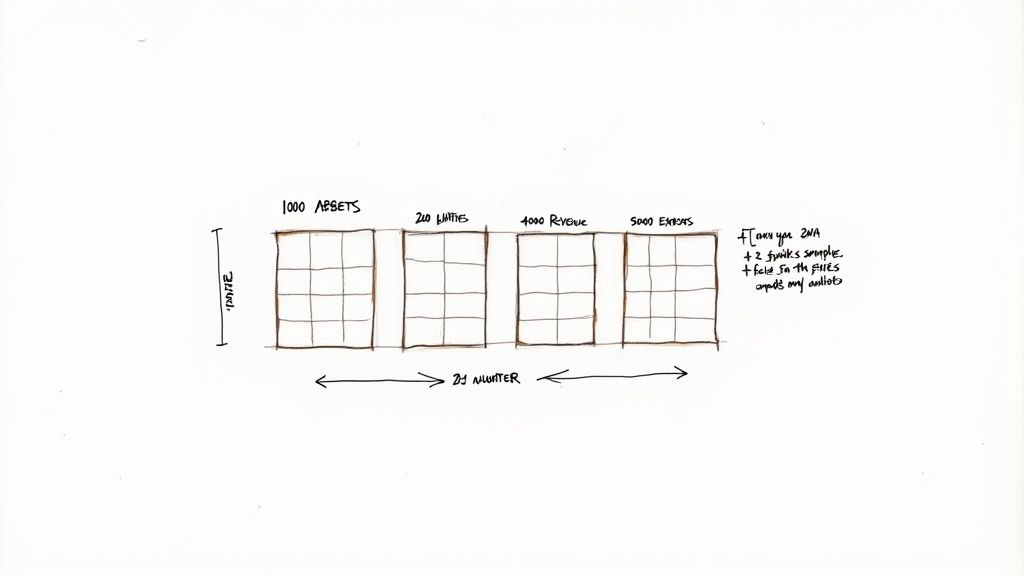

Designing a Smart Account Numbering System

Now that you have a handle on fund accounting, it’s time to build the practical framework for your chart of accounts: the numbering system. Think of it as the digital address for every financial transaction. A logical, well-organized numbering scheme brings order to your financials, makes data entry a breeze, and simplifies reporting down the line.

Most nonprofits lean on a standard four or five-digit numbering system. This isn't just a random choice; it’s a proven method for creating a consistent and scalable way to categorize every dollar and cent.

A smart numbering system is intuitive. At a glance, anyone on your team should be able to identify a transaction's category—whether it's an asset, a liability, revenue, or an expense—just by looking at the first digit of the account number.

That kind of clarity is crucial for correctly classifying and tracking all your financial activity, which is the foundation of the segmented reporting nonprofits rely on. Generally, the COA is organized numerically where Current Assets are numbered 1000-1999, Liabilities 2000-2999, Net Assets 3000-3999, Revenue 4000-4999, and Expenses 5000-9999. You can dive deeper into how to set up your nonprofit chart of accounts with this helpful guide.

Building a Logical Account Structure

The real beauty of a numerical system is its logical flow. When you group similar accounts into ranges, you create a COA that tells a clear financial story and helps ensure every transaction gets coded correctly right from the start.

Here’s a common high-level breakdown:

- 1000s - Assets: This range covers everything your church or nonprofit owns, from cash in the bank (like 1010) to fixed assets like buildings and property (like 1500).

- 2000s - Liabilities: Use this series for everything you owe, such as accounts payable (like 2010) or long-term debt on a building (like 2500).

- 3000s - Net Assets: This section reflects your organization’s net worth, with separate accounts for funds without donor restrictions (e.g., 3100) and with donor restrictions (e.g., 3200).

- 4000s - Revenue: All your income streams are categorized here, from individual contributions (e.g., 4100) to grant revenue (e.g., 4300).

- 5000s+ - Expenses: This is typically your largest category, tracking all your spending. It’s often broken down further by function—we’ll get to that in a minute.

Planning for Future Growth

One of the biggest mistakes I see organizations make is numbering their accounts consecutively—like 4001, 4002, 4003. It looks neat and tidy at first, but it completely boxes you in, leaving no room to add new accounts later without a major overhaul.

A much smarter practice is to leave intentional gaps between account numbers.

For example, you could set up your revenue accounts like this:

- 4100 - Individual Contributions

- 4150 - Corporate Contributions

- 4200 - Foundation Grants

This simple approach leaves 49 unused numbers between individual and corporate giving. That gives you plenty of breathing room to add more detailed contribution accounts in the future without having to re-number your entire chart.

Using Sub-Accounts for Granular Detail

Your main account numbers give you the high-level structure, but sub-accounts deliver the detail you need for truly meaningful reports. Sub-accounts let you break a broad category down into its more specific parts.

A classic example is payroll. Instead of one generic "Salaries" expense account, you can create sub-accounts to track spending with much greater precision:

- 5010 - Salaries and Wages (Parent Account)

- 5011 - Program Staff Salaries

- 5012 - Administrative Staff Salaries

- 5013 - Fundraising Staff Salaries

This simple technique makes it incredibly easy to see exactly how much you're spending on each functional area. That kind of detail is critical for completing your Form 990 and for making sharp, strategic budget decisions.

Practical Chart of Accounts Templates You Can Use

Theory is great, but let's be honest—it’s seeing a real chart of accounts for nonprofits in action that makes everything click. To help you bridge the gap between concept and creation, we've put together two practical, flexible templates.

Think of these not as strict blueprints but as solid starting points. They’re designed to be molded to fit the unique shape of your organization. One is for a small-to-medium nonprofit, and the other is tailored specifically for a church.

Sample Chart of Accounts for a Mid-Sized Nonprofit

This first example is built for an organization juggling multiple programs and funding sources, from foundation grants to individual gifts. Take a look at the numbering—see how there are gaps left intentionally? That’s to give you room to add new accounts later without messing up the whole system.

A well-organized chart of accounts like this is also the bedrock of good financial planning. It directly informs how you put together your financial roadmap, which you can see in action in this sample nonprofit budget template that relies on the same kind of structure.

Your chart of accounts isn't just a list for your bookkeeper. It's a strategic tool that should mirror how your organization actually operates, making financial data intuitive for program managers, development staff, and board members alike.

Below is a comprehensive yet adaptable chart of accounts template designed for a typical mid-sized nonprofit organization, covering key operational areas.

Sample Chart of Accounts for a Mid-Sized Nonprofit

| Account Number | Account Name | Account Type | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1000s | Assets | ||

| 1010 | Operating Checking Account | Asset | Main bank account for daily operations. |

| 1200 | Grants Receivable | Asset | Pledged grant funds not yet received. |

| 1500 | Buildings | Asset | Cost basis of physical property owned. |

| 1600 | Equipment | Asset | Value of computers, furniture, and other equipment. |

| 2000s | Liabilities | ||

| 2010 | Accounts Payable | Liability | Bills and invoices owed to vendors. |

| 2200 | Accrued Payroll | Liability | Wages earned by staff but not yet paid. |

| 2500 | Mortgage Payable | Liability | Long-term loan balance on property. |

| 3000s | Net Assets | ||

| 3100 | Net Assets Without Donor Restrictions | Net Asset | General funds available for any mission purpose. |

| 3200 | Net Assets With Donor Restrictions | Net Asset | Funds restricted by donors for specific programs or time. |

| 4000s | Revenue | ||

| 4100 | Individual Contributions | Revenue | Unrestricted donations from individual supporters. |

| 4300 | Foundation Grants | Revenue | Grant income from private foundations. |

| 4500 | Program Service Fees | Revenue | Earned income from services provided. |

| 5000s | Expenses | ||

| 5010 | Salaries and Wages | Expense | Gross pay for all staff members. |

| 5100 | Occupancy | Expense | Rent, utilities, and other facility costs. |

| 5200 | Program Supplies | Expense | Materials directly used in program delivery. |

| 5500 | Professional Fees | Expense | Payments for consultants, legal, or accounting services. |

This layout provides a clear, high-level view of the organization's financial components, ready for customization.

Sample Chart of Accounts for a Church

Our second template is designed with churches and faith-based ministries in mind. You’ll notice the revenue accounts are different, reflecting typical income streams like tithes, offerings, and designated giving.

The expense section is also customized for ministry operations, with accounts for things like mission trip costs and benevolence funds. This kind of structure is crucial for providing clear and transparent stewardship over the funds your congregation entrusts to you.

Sample Chart of Accounts for a Church

| Account Number | Account Name | Account Type | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1000s | Assets | ||

| 1010 | General Fund Checking | Asset | Primary bank account for operational expenses. |

| 1020 | Building Fund Savings | Asset | Savings account for capital campaign funds. |

| 2000s | Liabilities | ||

| 2010 | Accounts Payable | Liability | Unpaid invoices for church expenses. |

| 2250 | Pass-Through Funds Payable | Liability | Funds collected for another ministry and awaiting disbursement. |

| 3000s | Net Assets | ||

| 3100 | Net Assets - Undesignated | Net Asset | General funds without donor restrictions. |

| 3210 | Net Assets - Building Fund | Net Asset | Donor-restricted funds for building projects. |

| 3220 | Net Assets - Missions Fund | Net Asset | Donor-restricted funds for missions support. |

| 4000s | Revenue | ||

| 4010 | Tithes & Offerings - Undesignated | Revenue | General giving from the congregation. |

| 4020 | Designated Giving - Building Fund | Revenue | Contributions specifically for the building fund. |

| 4030 | Designated Giving - Missions | Revenue | Contributions specifically for missions. |

| 4200 | Facility Rental Income | Revenue | Income from renting church space to outside groups. |

| 5000s | Expenses | ||

| 5010 | Pastoral Salaries | Expense | Compensation for pastoral staff. |

| 5020 | Administrative Salaries | Expense | Compensation for office and support staff. |

| 5100 | Worship & Ministry Supplies | Expense | Costs for services, curriculum, and ministry events. |

| 5300 | Missions Trip Expenses | Expense | Costs associated with sending and supporting mission teams. |

| 5400 | Benevolence | Expense | Financial assistance provided to community members. |

These examples give you a solid foundation to build upon. The real magic happens when you adapt one of them to fit your specific programs, funding streams, and reporting needs. That's how you turn your chart of accounts into a tool that tells a clear and powerful financial story.

How a Dimensional COA Simplifies Your Reporting

As your church or nonprofit grows, your financial story gets a lot more complex. Suddenly, you're not just tracking basic income and expenses. You're juggling multiple programs, grants from different foundations, and maybe even activities across several locations. A traditional, linear chart of accounts just can’t keep up—it quickly becomes a tangled, confusing mess.

This is where a dimensional chart of accounts completely changes the game. Instead of creating a new account number for every single fundraising event or mission trip, this approach adds context to each transaction using simple "tags" or "dimensions."

Think of it like organizing your digital photos. The old way was to create rigid folders: "Youth Group Mission Trip 2023," "VBS 2023," "Building Fund Bake Sale 2023." A dimensional approach is like adding tags to each photo instead. A single picture from the mission trip could be tagged with #YouthMinistry, #SmithFamilyDonation, and #GuatemalaMission. It's a far more flexible and powerful way to see the whole picture.

From Account Bloat to Financial Clarity

The big problem with a traditional chart of accounts is that it forces you to create a new line item for every single reporting need. Let's say you need to track salaries for your after-school program, specifically paid for by the Miller Foundation grant. You might end up with an account like "5010-ASP-Miller." This leads to an explosion of accounts, making your COA incredibly long and a nightmare to manage.

A dimensional model avoids this mess entirely. You have one simple expense account, like 5010 - Salaries, and then you add the context with dimensions:

- Program: After-School Program

- Fund: Miller Foundation Grant

- Location: Community Center

This keeps your main chart of accounts lean and easy to read while giving you incredibly granular reporting. Consider this: a nonprofit with just 40 expense accounts across five locations, three countries, and twelve departments could end up with 7,200 account combinations in a linear system. That’s just not manageable. You can learn more about taming your COA with dimensions and see how this structure prevents that kind of overwhelming complexity.

By separating the 'what' (the expense account) from the 'why' (the dimensions), you unlock the ability to slice and dice your financial data in almost limitless ways, all without cluttering your core financial structure.

Unlocking Powerful, Multi-Layered Reports

The real magic of a dimensional COA happens when it's time to run reports. Because every single transaction carries this rich, contextual data, you can generate highly specific reports on the fly that would be impossible with a traditional setup. Your leadership team, board, or finance committee can finally get immediate answers to their most critical questions.

Imagine asking your accounting system questions like:

- "Show me all marketing expenses specifically for our after-school program."

- "What were the total direct costs for the Miller Foundation grant last quarter?"

- "How did our spring gala's fundraising efficiency compare to our year-end appeal?"

This kind of insight is invaluable for preparing grant reports, presenting at board meetings, and planning for the future. You're no longer just looking at a static record of the past; you're using your financial data as a dynamic tool to make smarter decisions. Of course, you need the right tools to make this happen. Exploring the best accounting software for nonprofit organizations will show you which platforms are built from the ground up to handle this modern, dimensional approach. It’s the key to turning financial complexity into strategic clarity.

How to Create or Update Your Chart of Accounts: A 5-Step Guide

Building or overhauling a chart of accounts for your nonprofit can feel like a daunting project. But with a clear plan, you can turn that tangled mess into a powerful tool for financial clarity. Breaking it down into manageable steps takes the anxiety out of the process.

Think of it less as an accounting exercise and more as creating a roadmap for your organization's financial story. Whether you’re starting fresh or updating a system that’s been around for years, this approach will help you build a COA that truly serves your mission.

Step 1: Start with the End in Mind—Your Reports

Before you even think about account numbers, ask yourself: What reports do we absolutely need to run? The entire purpose of a good COA is to make reporting easy and insightful. What are the most common questions your board, program managers, and grantors are asking?

Jot down a list of every report you rely on. It will likely include:

- Statement of Financial Position: The nonprofit version of a balance sheet.

- Statement of Activities: Your income statement, showing revenue and expenses.

- Statement of Functional Expenses: This is a big one for your Form 990. It breaks down every dollar into program, administrative, and fundraising costs.

- Grant-Specific Reports: What do your funders need to see to know their money was used as intended?

This list is your blueprint. Every single account and category you create from here on out should directly help you produce these reports without any complicated spreadsheet gymnastics.

Step 2: Take a Hard Look at Your Current Setup

With your reporting wish list in hand, it’s time to audit your existing COA. Where are the pain points? Be honest. Do you have dozens of accounts that haven't been touched in years? Are the account names so vague that no one knows what they’re for?

It's not just about spotting flaws; it's about understanding why the old system isn't working. Often, a COA has been patched together over a decade, with new accounts added on the fly. It no longer reflects how your organization actually operates.

Figure out which accounts are essential, which ones can be merged or deleted entirely, and where you’re missing the detail you need. This analysis will form the foundation of your new, cleaner structure.

Step 3: Design the New Framework

Now for the creative part. Using your reporting needs and the audit of your old system, start drafting the new COA. Begin by setting up a logical numbering system with plenty of room to grow. A classic structure works best:

- 1000s: Assets

- 2000s: Liabilities

- 3000s: Net Assets

- 4000s: Revenue

- 5000s+: Expenses

As you build, constantly check back against your reporting blueprint. For instance, if you need to report on functional expenses, make sure you create distinct expense accounts that clearly align with your program, administrative, and fundraising activities. This will make pulling your Statement of Functional Expenses a simple, one-click process.

Step 4: Map the Old to the New and Move Your Data

This is where the rubber meets the road. Create a "map" that connects every old account to its new home. A simple spreadsheet is perfect for this—just two columns: "Old Account Number" and "New Account Number."

This mapping document is your lifeline during the transition. It ensures your historical data lands in the right place and gives you a clean cut-over.

Modern accounting software can be a huge help here. Platforms like Grain often let you import your new COA structure and then use your mapping sheet to reclassify past transactions in bulk. This saves countless hours of manual data entry and minimizes the risk of human error.

Step 5: Go Live and Train Your Team

Once the new system is up and running, the final—and most important—step is training. Your team can't use the new COA effectively if they don't understand the logic behind it.

Walk them through the structure, show them how to code transactions correctly, and explain where to find the information they need. Provide simple, clear documentation, like a one-page guide explaining what each account range is for. A little training up front ensures everyone uses the system consistently, unlocking its true potential for clear and confident financial management.

Common Questions About Nonprofit Chart of Accounts

As you start building or tweaking your financial systems, some very practical questions are bound to pop up. When it comes to a chart of accounts for nonprofits, the real trick is balancing useful detail with day-to-day usability. Let's tackle some of the most common hurdles organizations run into with clear, straightforward answers.

What Is the Biggest Mistake Nonprofits Make with Their COA?

Hands down, the most common pitfall is failing to find the right balance. So many organizations swing to one of two extremes: their chart of accounts is either way too simple or wildly too complex. Both create massive headaches down the road.

A COA that’s too simple, with just a handful of generic expense accounts, makes any kind of meaningful reporting impossible. You can't show your board how much a specific program actually cost, and you certainly can't prove to a funder that you used their grant money as intended.

On the other side of the spectrum, a COA with thousands of hyper-specific accounts becomes an absolute beast to manage. This usually happens when an organization creates a new general ledger account for every single grant or department instead of using other tools like fund codes or classes. The result? A cluttered, confusing system that’s a nightmare to navigate and practically invites coding errors.

The key isn't complexity; it's clarity. A great chart of accounts is one that is detailed enough to answer your most important financial questions but simple enough for your team to use accurately every day.

Finding that sweet spot is everything. Your COA should be a direct reflection of how your organization actually works and what you need to report on—no more, no less. That alignment is what makes your financial data both useful and manageable.

How Often Should We Review Our Chart of Accounts?

Think of your chart of accounts as a living document, not something you set in stone and forget. It's a great practice to give it a formal review annually, and the perfect time to do this is while you're working on your yearly budget. This gives you a natural opportunity to step back and ask, "Does this structure still make sense for our programs and funding?"

Now, an annual review doesn't mean you need to blow things up and start over every year. You should only plan for a major overhaul when your organization goes through a significant strategic change, like:

- Launching a major new program.

- Receiving a complex federal grant with very specific tracking rules.

- Expanding your operations to a new city or state.

For minor tweaks—like adding a new expense account for a software subscription you just bought—you can do that whenever the need arises. The annual review is really for making sure the big-picture structure is still serving you well.

Can We Use the Same COA for Budgeting and Our Audit?

Absolutely. In fact, you should. A well-designed chart of accounts is the glue that holds everything together—it connects your daily bookkeeping, your annual budget, and your year-end audit. It should be the single source of truth for all your financial data.

The structure of your COA provides the exact line items you'll use to build out your budget. As your team codes transactions to these accounts throughout the year, that data flows right into your financial reports. Then, when the auditors arrive, you can hand them clean, organized data that perfectly matches the categories on your financial statements. That consistency makes their job easier and builds a ton of trust.

Ready to build a chart of accounts that truly works for your church? Grain offers a native fund accounting architecture designed from the ground up to provide the clarity and control ministries need. See how our system can simplify your financial stewardship and deliver trustworthy reports. Join the Grain waitlist today!

Ready to simplify your church finances?

Join the waitlist for early access to Grain - modern fund accounting built for ministry.